Intensive Pre-Stem Cell Transplant Regimen May be Best for Younger Patients with AML, MDS

May 26, 2017, by NCI Staff

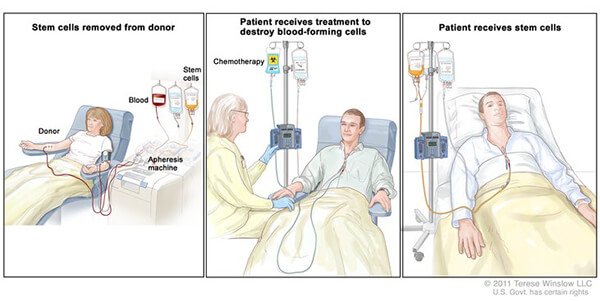

Results from a large phase III clinical trial suggest that a highly intensive preparatory, or conditioning, regimen should be used for younger patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) preparing to undergo an allogeneic stem cell transplant.

Patients in the trial who received this standard "myeloablative" conditioning regimen, which entails high doses of chemotherapy and/or radiation, were far less likely to experience a disease relapse after the stem cell transplant than patients who received less aggressive, or reduced-intensity, conditioning regimens.

The trial was stopped early, after accruing approximately three-quarters of the total number of patients originally planned, because of the high number of relapses in patients who received the reduced-intensity regimen.

Fewer patients in the reduced-intensity regimen group than the standard-intensity group died as a result of the treatment, the trial's lead investigator, Bart Scott, M.D., of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and his colleagues reported in the April 10, 2017 Journal of Clinical Oncology. But the difference was not enough to offset the group's much higher rate of cancer relapse.

Researchers are developing and testing new options to treat patients who have a relapse after a stem cell transplant, Dr. Scott said. But to date little progress has been made, which is why the high relapse rate in the trial's reduced-intensity conditioning group was so concerning.

"Post-transplant relapses are just historically very difficult to treat," he said. "Patients who relapse have a very poor prognosis."

Dr. Scott said he considered the trial's results to be definitive, clearly showing that myeloablative conditioning should be the standard in younger patients who are healthy enough to tolerate it.

A Trend Toward Reduced-Intensity Regimens

Most patients with AML and MDS under the age of 65 whose disease goes into remission following initial, or induction, treatment will go on to receive a stem cell transplant. For a substantial portion of these patients, an allogeneic stem cell transplant can cure their disease.

In younger and otherwise healthy patients, myeloablative regimens have traditionally been preferred, explained Steven Pavletic, M.D., of the Experimental Transplantation and Immunology Branch in NCI's Center for Cancer Research, who was not involved in the trial.

However, not only can these regimens be very toxic, but in a modest percentage of patients they can be fatal.

Myeloablative regimens are used for their efficacy in killing any residual cancer cells left after induction therapy and in allowing the transplanted stem cells to engraft—that is, take up residence in the bone marrow and begin producing healthy red and white blood cells. Engraftment is a key predictor of long-term survival.

Because of the toxicity and related risk of death associated with myeloablative regimens, reduced-intensity regimens are usually reserved for older patients, in whom AML is also more common, Dr. Pavletic continued.

But more recently "there has been a push in practice to use milder regimens in [younger] patients as well," he said.

Some studies have suggested that long-term survival rates are similar for patients treated with myeloablative and reduced-intensity regimens. But no randomized trials in younger patients had been done to provide more definitive evidence.

Trial Stopped Early

The trial was conducted by the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network, which is funded in part by NCI. Most of the 272 patients who were enrolled in the trial before it was stopped had AML. All patients in the trial had disease that had gone into remission after induction therapy.

Participants, all of whom were aged 18 or older, were randomly assigned to one of the two conditioning regimens. No single conditioning regimen was required to be used in the trial, although each participating center used specific myeloablative and reduced-intensity regimens.

At 18 months follow-up, the rate of deaths attributed to conditioning regimen was much lower in patients who received the reduced-intensity regimen than in those who received the myeloablative regimen: 4.4% versus 15.8%. This difference was less than the researchers had expected to see, Dr. Scott said, noting that traditionally the rate of deaths associated with myeloablative regimens is closer to 20%.

He attributed the lower mortality in the trial's myeloablative arm to the improvements being made "in delivering high-dose chemotherapy and radiation therapy with less toxicity."

The overall relapse rate was 67.8% in patients who received the reduced-intensity regimen versus 47.3% in those who received the myeloablative regimen. For patients with AML specifically, it was 65.2% versus 45.3%.

It was the trial's data safety monitoring board that, based on the substantial difference in relapse rates between the groups, called for the trial to be stopped early. The dramatically higher relapse rate in the reduced-intensity group caught the research team by surprise, Dr. Scott noted.

"That speaks to why it's necessary to do these phase III randomized clinical trials, because what you might expect to be true can be proven to not be true," he said.

More patients who underwent the myeloablative regimen were alive at 18 months follow-up. The difference in survival was not statistically significant for the overall patient population, but it was for patients with AML, Dr. Scott said.

The survival difference between the groups is likely to expand, Dr. Scott and his colleagues noted. Mortality in patients who had a relapse and were still alive when the trial was halted "is expected to be high," they wrote.

Practice Changing

The trial's findings are "practice changing," Dr. Pavletic said, and should "put an end" to the trend of using reduced-intensity conditioning in younger, fit patients.

He offered some caveats, however. The trial doesn't answer, for instance, if the results might be different with other types of reduced-intensity conditioning regimens.

He also noted that it would be interesting to see if the risk of relapse associated with a reduced-intensity regimen is different in patients who have no minimal residual disease—that is, the presence of low levels of cancer cells despite no symptoms or other overt signs of cancer—after induction therapy.

Studies have suggested that patients with minimal residual disease have an increased risk of post-transplant disease relapse. Dr. Scott said that investigators plan to do ongoing analyses of the trial data that take into account factors such as minimal residual disease.

But not all of the participating centers collected these data, he said, which will limit the researchers' ability to reach firm conclusions about the impact of different patient factors on relapse risk.

Nevertheless, the results from this trial "set the stage for developing and testing new-generation, reduced-intensity conditioning regimens for AML," Dr. Pavletic said, including those that use targeted therapies and immunotherapies.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario